When Riemann pulled into his parking spot the mist was still tight over the quad like gauze over a fresh wound. The sun was still making a spectacle of rising over the collegiate sprawl of Cornell University, golden rays shining through the tangled canopy of oaks overhead as wind whispered with the voice of rustling autumn leaves. He stepped out of his vintage Volvo wrapped in a wool coat that made him look vaguely monastic, and he surveyed the campus with pale, watery blue eyes that had the unsettling quality of being both intensely observant and indifferently distant, as though taking inventory of each blade of grass, not by its shade of green but by its angular defiance against the geometry of the lawn. He moved with the gait of a man who had once been an athlete, or at least an enthusiastic weekend jogger, but whose knees and convictions had since conspired to divest him of the habit. His midsection wasn’t soft, not exactly, but it carried an insidious thickness, the kind that implied he spent more time behind a desk than astride an exercise bike. The crown of his head was a barren peninsula surrounded by a thinning sea of sandy-brown hair, meticulously combed to distract from the follicular retreat.

Born in a Midwestern town whose name was so generic it might as well have been generated by an algorithm, Riemann had always seemed a man with one foot in the soil and the other in abstraction. His Scotch affinity, born of evenings spent nursing single malts in the company of textbooks and Bach, betrayed a heritage he knew only through the glossy brochure of direct-to-consumer genetic testing and the awkward braggadocio of distant uncles. When asked about his roots, he would cock his head like a terrier and say “Scottish,” with a bemused air, as if the notion itself were an inside joke between him and the ghosts of the Highlands. His clean-shaven face bore a paleness that suggested he spent more time in front of the glow of a computer screen than under the warmth of the sun. His skin was punctuated by fine lines that hinted at a life spent squinting at small text and bigger problems, as well as by a perpetual redness on the bridge of his nose from glasses he pushed back in perpetuity. His eyes, a pale, watery blue, carried the sharpness of someone who could analyze a conversation as quickly as a dataset, and often with less patience for error. Standing there in the gauzy light of the morning, coat buttoned to the neck as if warding off some existential draft, Riemann was a man at once unremarkable and impossible to ignore. He exuded a peculiar gravity, the sort that made people pause mid-thought when he entered a room, unsure whether to fear his judgment or invite it. He had about him the air of a man who had read too many books and lived too few of their lessons, and his presence seemed less like something you encountered and more like a sudden realization you’d been trying to avoid.

Malott Hall, home to the Department of Mathematics, stood with the resolute, modernist simplicity of mid-century architecture. Built in 1963, its pale concrete façade and long, utilitarian windows overlooked the quad with an air of apathetic permanence. Inside, the sterile corridors hummed with the sound of fluorescent lights and the muffled footsteps of students scurrying to early lectures. Riemann’s office was on the third floor, a narrow room that smelled of dry paper and black tea left forgotten on a windowsill, its only decoration a sprawling whiteboard with manic scrawlings that could be mistaken for the ravings of a madman or the compositions of a genius, depending on who was looking at it. It was covered edge to edge with yesterday’s equations, each staggering into the other like drunken revelers at a festival.

He sat at his desk—a topographical nightmare of stacked papers, open books, nearly spent pens, empty mugs, crumpled sticky notes scrawled with half-formed equations, a cracked protractor, a slide rule yellowed with age, a jar of paperclips, a small framed photo commemorating the occasion when he had the great fortune of meeting Sir Roger Penrose. He held his gaze on a particular equation that always seemed to catch his eye:

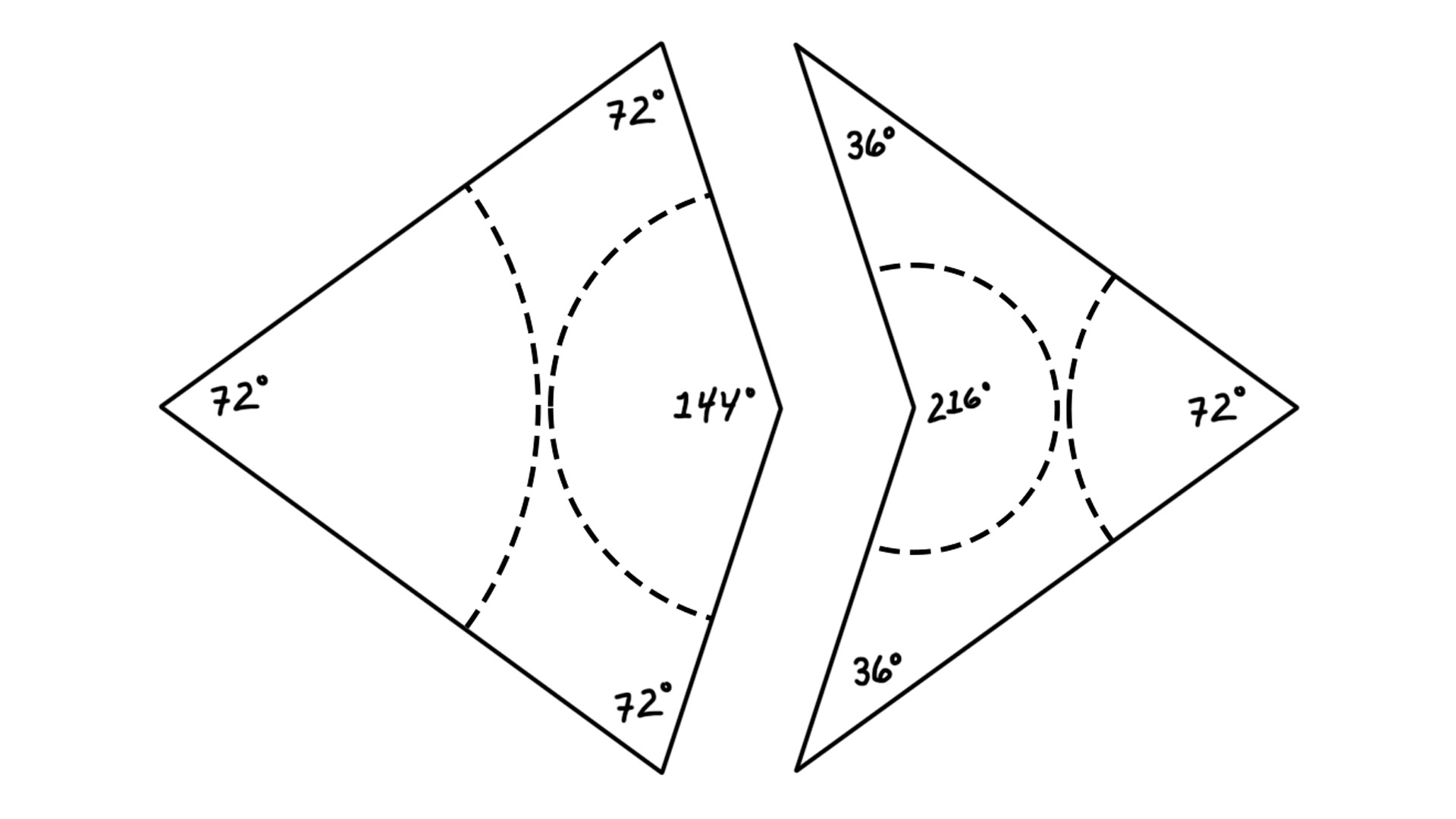

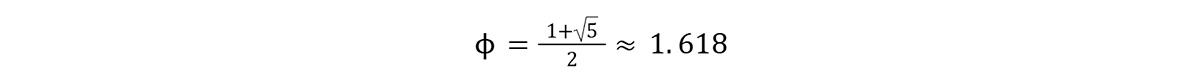

The golden ratio—that curious number which arises when the universe slouches slightly toward beauty rather than brute functionality; the peculiar order to which his beloved Penrose tiling, with its quadrilateral kites and darts (those shapes that conspire to form an infinite, aperiodic rebellion against the tiresome tyranny of regularity) is beholden. The angles—72° here, 36° there—dictate the blueprint, an eternal structure where no pattern ever recurs. The angles—72° here, 36° there—dictate the blueprint, an eternal structure where no pattern ever recurs.

Yet this isn’t chaos—it’s a precise, deliberate unfolding, each kite and dart giving rise to others, constrained by their geometry into forms that seem self-replicating yet never truly repeat. Like an ouroboros of angles and vertices, their interplay is dictated by rules that forbid some combinations while compelling others, constructing a vast, intricate architecture of order within apparent randomness.

You could chart it with equations if you liked, perhaps something involving phi multiplied by the cosine of theta and an iterative algorithm, but it’s not the math that matters—what matters is the way it refuses to submit to grids or reason, a pattern that mocks the very idea of pattern, infinite and strange as the stars themselves.

“Doctor Riemann,” a voice interrupted his reverie. The door creaked as it opened to reveal Dana Malach, a graduate student whose undaunted dedication to her research was equaled only by her sharp wit and unapologetic directness. Dana served as Riemann’s research assistant, and he returned the favor by acting as her faculty sponsor, supervising her thesis research.

“Miss Malach,” Riemann acknowledged without turning. He waved a hand toward a nearby chair, cluttered with old issues of The Mathematical Intelligencer and a cracked mug bearing the slogan There’s No Place Like Home (in Hilbert Space). She brushed the debris aside, sat with a huff, and adjusted her glasses, which had a habit of slipping down her nose at the most inopportune moments. The frames were unassuming, sleek black with understated gold accents, striking a careful balance between pragmatism and elegance. Their oversized lenses gave her a sharp, owlish air, accentuating her intellectual presence. Yet, in the play of light and angle, they subtly transformed the shape of her eyes, lending them a delicate slant that seemed almost foreign—an optical illusion, perhaps, but one that hinted, fleetingly, at something curious and unknowable. Coupled with her tousled dark hair and porcelain complexion, the overall effect was undeniably alluring.

“I’ve reviewed the first draft of your paper,” she began, voice thin as wire, stretched taut by the weight of unspoken hesitations. “The one on integrating out M2 states and the connection to Penrose tiling geometries. It’s … compelling, to say the least.”

Compelling. The word rolled around in his mind, a warm, ironic touch that contrasted starkly with the cold logic of the equations by which he lived. His eyes darted to her hands as she gestured, slim fingers tracing invisible patterns in the air. A dissonant thought sparked in his mind—uninvited, unwelcome—but he crushed it beneath the weight of self-reprimand. Control, Sebastian.

Riemann smirked, a tight, humorless thing that made her shift in her seat. “Compelling,” he echoed, testing the heft of the word as if it might reveal something about her—or him. “Did you spot the anomaly in section four?”

Dana pursed her lips. “The assumption about the connection between the duality symmetry in the free energy and the aperiodic structure of Penrose tilings? I did. I think it needs more proof, especially if you’re suggesting—”

“I’m not suggesting,” he cut in, eyes finally snapping to hers with a startling sharpness. “I’m outright stating. The duality isn’t a coincidence—it’s the framework. There’s a pattern beneath the chaos. You can’t see it, not yet, but when you do…” His voice trailed off, leaving her grasping at the silence that followed.

She blinked twice, then her expression hardened. “It needs more proof,” she asserted.

She gathered her notes, and Riemann couldn’t help but let his gaze linger a moment longer than necessary. Her movements were graceful, each delicate flick of her wrist as she stacked the papers sending a jolt of awareness through him. The way her hair fell in soft waves around her face, the slight furrow of concentration on her brow, all of it combined to create a captivating image that he found hard to tear his eyes away from. His thoughts strayed to places they shouldn’t, imagining what it would be like to run his fingers through that silky dark hair, to feel the warmth of her Victorian skin under his touch. He shook his head, trying to dispel the inappropriate fantasies that threatened to take root in his mind. With a quick cough to clear his throat, he forced himself to look away as she finished gathering her things and left the room.

Outside, students milled about, their laughter and complaints mixing with the gentle drone of leaf blowers. Riemann barely heard them. The world outside his office was an echo chamber of trivialities—weekend plans, awkward flirtations, the banal melodrama of youth. Here, in this sanctuary of chalk dust and crumpled graph paper, he existed on a higher plane, where numbers weren’t just numbers but keys to a kingdom he alone could envision. The clock on the wall ticked like a metronome, each beat a reminder of time slipping away. His mind was already buzzing with new possibilities. Dana’s words lingered in the air, ripe with doubt and skepticism—but he had grown accustomed to the ebb and flow of skepticism and revelation, each rejection fueling his obsession further. The Penrose tilings beckoned to him, their intricate patterns whispering secrets he felt only he could decipher. Fractals danced behind his closed eyelids, where kites and darts morphed into celestial shapes, weaving a fabric that transcended dimensions. The world around him faded away, leaving only the pulsating hum of numbers resonating in his ears. He would unlock the hidden geometry of the universe, he had no doubt. Peer review be damned, Riemann often thought. He would show them all. The critics who dismissed his theories as flights of fancy—who dismissed him as a circle-squarer—would soon have no choice but to yield to the brilliance of his discoveries.

The heavy metal door to Riemann’s office once again creaked on its old hinges. He looked up to see Sabine standing in the doorway, a vision of elegance and intellect, her presence commanding attention even in the cluttered chaos of Riemann’s office.

“Sebastian,” she spoke softly. “I hope I’m not interrupting anything.”

Riemann scrambled to bring himself back to reality as he gestured for her to enter. “Not at all, Sabine. Please, come in.”

Doctor Sabine Eraclito moved into the room like an idea taking shape in the mind, her steps both deliberate and hesitant, as if testing the ground for philosophical solidity. She paused just inside the doorway, glancing at the scattered ruins of Riemann’s workspace. Her gaze lingered on the whiteboard, the sprawling lattice of equations that seemed to crawl and spread like ivy on the wall, then on the bookshelves groaning under the weight of dense tomes, their spines embossed with arcane titles. “You live as if entropy were an aesthetic,” she said, her voice lilting with amusement. She adjusted the strap of her leather satchel, a bag so worn and patched that it seemed more artifact than accessory. “I am assuming that’s the point, no?”

Riemann leaned back in his chair, his fingers steepled beneath his chin. “If you’re here to critique my office, Sabine, you’re about two semesters too late. Dana’s already conducted a full rhetorical takedown—complete with visual aids, no less!”

Sabine let a laugh escape, soft and melodic, rich with that distinct Italian warmth. It was a laugh that seemed to belong in better, fresher air than what wafted here. “Ah, but no! I am here to make sure you have not forgotten tonight’s concert. Remember? Viktor’s brilliant idea to, how does he put it, ‘expand our intellectual palettes.’ Which is to say, an excuse for him to argue with the musicians during intermission.”

“The concert. Right. Viktor and his crusade against polytonality.”

“Esatto!” Sabine said, stepping closer to his desk and leaning on its edge with casual familiarity. “And tonight, he will have quite the sparring partner. Jules Cardini is the headliner. You know, the most avant-garde modernist composer since—well, take your pick. Schönberg, Xenakis, maybe Ives on a particularly mischievous day. His Symphony for the Age of Dust has been called his most daring work. Even Cardini’s critics are begrudgingly calling it visionary.”

Riemann smirked as his fingers tapped a rhythm against the arm of his chair. “Ah, yes. Cardini. The one who supposedly composes by algorithm and claims his music is a reflection of the universe’s inherent futility.”

“Precisely why you will love it,” Sabine countered. “Besides, you promised. And if this does not sway you, we are going for drinks after. Viktor found some obscure place with cocktails named after mathematical conjectures. I think one of them involves gin and a Möbius strip. Intriguing, no?”

Riemann chuckled. “So you came here to strong-arm me into an evening of nihilistic symphonies and overpriced beverages.”

“But of course. What are friends for?” Sabine perched herself on the corner of his desk, her hands folded neatly in her lap. The sunlight filtering through the narrow window cast sharp, geometric shadows across her face, accentuating her distinctly Mediterranean features—the elegant curve of an aquiline nose, high cheekbones that carried a whisper of Renaissance sculptures, and dark, expressive eyes that seemed to hold entire libraries of unspoken thought. “You have been buried in this,” she gestured broadly at the equations and books, “for how many months now? You need a break, Sebastian. Even Grothendieck had to stop and have a spritzer every once in a while, no?”

Riemann’s smirk faded, replaced by something more thoughtful. “Do you ever wonder,” he began, lowering his voice, “if the things we study, the patterns we chase—they’re leading exactly nowhere? That maybe the answers we’re looking for aren’t answers at all, but walls we keep running into because it’s just impossible for us to imagine the absence of a door?”

Sabine’s dark eyes narrowed to slits. “You are speaking of Gödel now, no? The idea that no system, no matter how elegant, can ever fully explain itself?”

Riemann nodded. “Cardini might have a point. The futility of it all. Not in the sense that it’s meaningless, but that meaning itself might be a mirage.”

Sabine let the silence stretch for a moment, her expression contemplative. “Ah, and yet,” she said softly, “we keep looking, don’t we? For doors. For cracks in the wall. Perhaps it’s not about finding them, but the act of searching itself.”

Riemann chuffed. “But is that enough? Will that ever be enough?”

“The universe does not owe us its secrets, Sebastian. The act of searching is the only answer it has ever freely given.” She smiled warmly. “That will be enough if you let it.” Her words hung in the air, a kind of philosophical benediction that neither of them dared disturb. Finally, she straightened, brushed an invisible speck of dust from her skirt, and turned to leave.

“Be ready by seven,” she said, her tone light but her eyes still bearing the load of their conversation. “And please do not wear that coat. It makes you look like you have taken a vow of silence.”

Riemann watched her go. He leaned forward, resting his elbows on his desk and staring once more at the endless sprawl of equations on the whiteboard. The golden ratio. The Penrose tiles. The kites and the darts. He thought of Sabine’s words, of doors and walls, of cracks and light. And for the first time in weeks, he felt the stirrings of something that seemed like hope—or possibly inspiration, which was, perhaps, even better.